"I'M ASKING YOU TO BELIEVE. Not just in my ability to bring about real change in Washington...I'm asking you to believe in yours".

Barack Obama Campaign '08 Website, at: http://www.barackobama.com/index.php

"I want to campaign the same way I govern, which is to respond directly and forcefully with the truth,"~ Barack Obama, 11/08/07, at: http://factcheck.barackobama.com/

Mr. Obama's logo has received accolades from members of the public interested in its 'symbolism'. At least one citizen has remarked,

"Yesterday afternoon, I waited at a red light behind a car with an Obama bumper sticker, and I was really impressed with Obama's logo. The capital O in his surname becomes an encompassing circle, which symbolizes both social communion and the integration of the self. The rising sun symbolizes birth and rebirth; the beginning of a season of growth; the banishment of darkness. Consider how fitting it is that the synoptic gospels state the women found the empty tomb at dawn in the springtime. The encompassing circle also fits with this, as it symbolizes the birth canal, through which new life enters the world. The plowed field symbolizes nature's bounty (which obviously belongs equally to us all) and reminds us of our debt to those who work to bring that bounty to our tables. It evokes quiet pride in the hearts of small town and rural Americans and strikes a chord of back-to-the-land longing in the hearts of post-hippie environmentalists."

See: Raymund Eich, Houston, The Transhuman Comedy -Raymund Eich's freelance futurism for fun and profit, at: http://www.sff.net/people/raymund/2008/04/obamas-logo.html .

It seems that the Mr. Obama and his campaign have focused more on conveying empty 'symbolism' and fostering 'belief' in any 'possible' future other than that which it deems likely to follow from the present, than on sharing with the American public the reality of today and the likely options for probable future outcomes. In other words, Mr. Obama has intentionally not been very clear about what 'changes' he envisions and why they are necessary. What is his true agenda? What are his ultimate objectives? Why has he not been forthcoming about his 'new' ideas for 'change'? What is Mr. Obama truly hiding through is opaque and oblique references to 'change you can believe in'? How many of Mr. Obama's idea's are actually 'new'?

One of the most remarkable aspects of the radical 'change' advocated by Mr. Obama is its unlimited and undefined breadth and scope - for all intensive purposes GLOBAL in magnitude. In fact, the radical 'change' called for by Mr. Obama appears to be common 'change for change-sake', NOT 'change' for the betterment of the U.S.

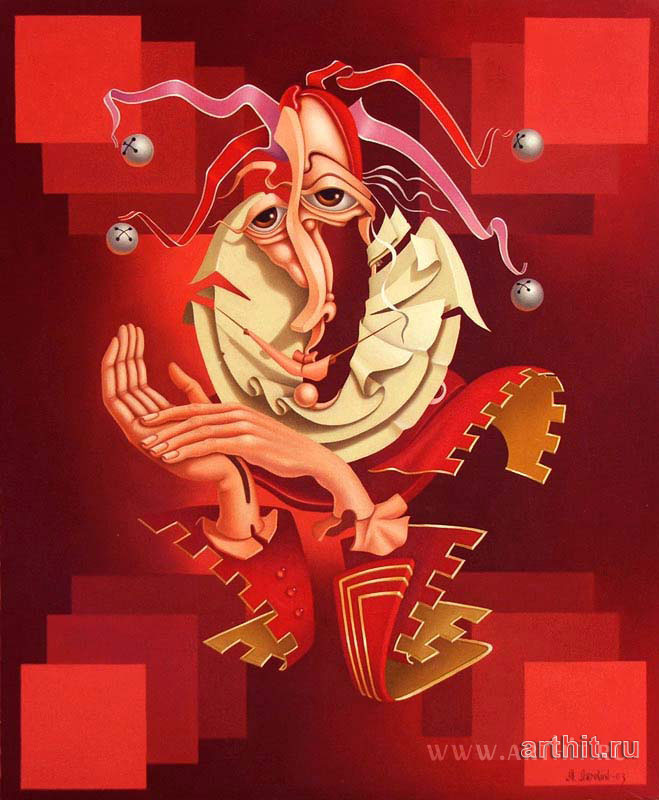

To reiterate, it is arguable that 'Obama Change' is merely for 'change from the status quo' - in culture, science, economics, law and politics. In this regard, 'Obama Change' can be compared with and linked back to the popular 'Surrealist Movement' of the early 20th century which encompassed the political, social and economic spheres of transnational society. Most people are familiar with surrealist art. For example:

However, as is clear from a recent article appearing in the French magazine Le Monde Dipomatique, the Surrealist Movement is much, much more than just art. Rather, it is comprised of a transnational political movement that sought change at any cost for any reason against any status quo.

"It is almost impossible to paint a true picture of surrealism, one

that respects the breadth of its debates and the limitlessness of its boundaries, reconstructs the movement in all its aberrant and contradictory glory and does justice to the depth of its artistic, social and political speculations. It is easy to lose our bearings, limit the scope of word or gesture, and let the door of fantasy swing closed. If its magic cannot be depicted for what it is - fleeting, shifting, fugitive - what is left? Since surrealism was not only an artistic movement but also a moment in political history and a passionate human adventure, how can it slot neatly into the curatorial or academic category of art history? The formal, aesthetic view will triumph and the political dimension be pushed aside as irrelevant to formal considerations. This obliteration of the faintest trace of surrealism’s political programme is contrary to the nature of the movement and the works it inspired."

that respects the breadth of its debates and the limitlessness of its boundaries, reconstructs the movement in all its aberrant and contradictory glory and does justice to the depth of its artistic, social and political speculations. It is easy to lose our bearings, limit the scope of word or gesture, and let the door of fantasy swing closed. If its magic cannot be depicted for what it is - fleeting, shifting, fugitive - what is left? Since surrealism was not only an artistic movement but also a moment in political history and a passionate human adventure, how can it slot neatly into the curatorial or academic category of art history? The formal, aesthetic view will triumph and the political dimension be pushed aside as irrelevant to formal considerations. This obliteration of the faintest trace of surrealism’s political programme is contrary to the nature of the movement and the works it inspired."...To sweep the movement’s active ambitions aside is to destroy both the dream and its harvest and render them ineffectual, or diverting. As André Breton wrote in The Political Position of Surrealism (1935): “Those modern poets and artists . . . who consciously aspire to work towards a new and better world must at all costs struggle against the current that seeks to sweep them away to a place where they become mere entertainers whom the bourgeoisie can define as they please (just as they tried to redefine Baudelaire and Rimbaud as Catholic poets once they were dead).”

"...Surrealism’s heritage, if it must have one, surely lies in this duty to reject, in its unique way of looking at the world, in a philosophy that reconciled action and dream. It has nothing to do with the triviality of a deliberate and profitable scheme to produce artworks..."

"Once surrealism receded into history, critics lost sight of its black cloak of revolt and humour, its adolescent rage and imperious desire to change the world. During the late 1920s surrealists fiercely opposed colonialism and discussed whether to join the communist party; throughout the 1930s they fought against fascism and Stalinism; during the second world war they were involved in the French resistance; in the 1950s they joined the anarchists; in 1960 they signed the Manifesto of the 121 (supporting the right to refuse to fight in the war in Algeria); they were involved in the revolutionary events of 1968. Successive surrealist groups gave their hearts to (or at least participated in) all the major political debates of the 20th century, including Jean-Paul Sartre’s call for engagement. By ignoring surrealism’s revolutionary vocation and the political commitment of the painters and poets who made it live, museums, collectors, critics and historians have forced it into the narrow mould of a movement whose sole purpose was to manufacture works of art."

"...Surrealism’s heritage, if it must have one, surely lies in this duty to reject, in its unique way of looking at the world, in a philosophy that reconciled action and dream. It has nothing to do with the triviality of a deliberate and profitable scheme to produce artworks..."

"...Our days are numbered, our identity is fixed, our imagination and our sexuality are limited; the horizon is closing in on us when it should be opening out to let the night of dreams encroach on day. A sense of wonder cannot be taught, it can only be created from endlessly renewed freedom and fury. Perhaps it has become almost an obscenity to mention revolution or class struggle. But there are still disturbing echoes to the words that Breton wrote in 1925, in issue 4 of La Révolution surréaliste: “Our hands cannot cling tightly enough to the rope of fire that stretches up the black mountain. Who is this who wants to use us and make us contribute to the abominable comfort of this world? Let it be known: we want no part in mankind’s attack on mankind. We have no civic convictions. In the current state of society in Europe, we remain committed in principle to any revolutionary activity whatsoever, even if its roots are in class struggle, provided only that it goes far enough.”

See: Vincent Gille, Surrealism in the Real World, Le Monde Diplomatique (May 19, 2005), at:

No comments:

Post a Comment